History of Azulejos

See the Azulejos gallery

"Azulejo" is a word used in Spain and Portugal to designate a glazed tile: a terracotta tile covered with an opaque glazing. In these two countries, azulejos have been frequently used since the 13th century to cover and decorate walls, fountains, pavements, ceilings, vaults, baths, or fireplaces.

Etymology This word comes from Arabic الزليج "al zulaycha" that means little polished stone, and not "azul" blue, as it is often said. It is true that there are many blue azulejos, and that can explain this confusion, but, historically, the first glazed tiles that appeared in Spain in the 13th c. where mainly green, brown, and yellow. Why "little polished stone"? Because the idea was first to reproduce the Greco-Roman mosaics from the Middle East or North Africa, not by assembling small pieces of polished marble ("tesserae"), but fragments of coloured glazed tiles. Understandably, it takes less effort to cut a local handmade tile, than to polish pieces of marbles coming from distant places! Those familiar with Morocco have necessarily seen zellige, a type of mosaic made with small pieces of coloured glazed tiles. In this country, "zellij" are still produced to cover floors, walls, swimming pools, bathrooms, etc. This ancient craft is still very much alive in Morocco, most artisans being in Fez. Moroccan "zillij" and Hispanic "azulejos" share the same etymology, and the same parentage with mosaic.

Oriental origins The first known glazed tiles come from Egypt and Mesopotamia. In 2620 BC, Pharaoh Djoser, founder of the 3rd dynasty, built in Saqqarah by his architect Imhotep a pyramid whose galleries leading to the funerary chamber are covered by green glazed tiles with yellow lines imitating papyrus stems. Glaze, sometimes called "enamel", which is a thin glass coating rendered opaque, is therefore an ancient discovery. However, in antiquity, this technique was exclusively oriental, and in fact, was subsequently lost: the Greco-Roman world did not of know it. To decorate surfaces, Greeks and Romans developed several techniques such as painting on wet plaster ("fresco"), or stucco, or mosaic.

The rediscovery of opaque glaze In the 9th century, the Sassanid Persians rediscovered the use of tin as an opacifyer for glass, and they started to produce once again glazed tiles with an opaque glazing. Their Abbasid neighbours - Baghdad was their capital - also started to master this technique, which later on diffused throughout the Arab-Muslim world, from the gates of Constantinople to Spain. Under the Fatimids, Egyptian potters decorated with tiles many walls of palaces, tombs, or mosques, in Cairo.

Europe through Spain It is therefore the Arabs who brought this art to Europe from the Middle-East. The first use of glazed tiles consisted of geometric assemblages of pieces of cut tiles ("alicatado"). Beautiful examples can still be admired in place at the Alhambra in Granada. The patterns used are complex and reflect the taste for geometry in the Islamic world. However, alicatado is a process that remains expensive because it requires a lot of manual work for cutting tiles. And the process of cutting generates a significant waste of tiles. To overcome these drawbacks, the craftsmen eventually imagined applying coloured glazes directly on clay tiles, but separating zones to avoid the mixing of colours. These separations are made by drawing the contours with a fatty substance mixed with a black pigment (manganese oxide). This mixture turns into a black thin line after baking. This process is called in Spain "cuerda seca". The tiles produced by this method have mostly Moorish patterns, similar to compositions made with alicatado. Patterns have often a beautiful radial style; sometimes they have what we would now call a cubist effect. Around 1500, the process of cuerda seca was replaced by two similar techniques. With arista tiles the partitioning is made by fine clay ridges. With cuenca tiles, it is done with furrows. In both cases, a wood mould carved with the pattern is used to stamp the soft clay tile. Therefore there is no more black line between the elements of different colours. These two techniques were intended to produce low cost alicatados. The main centres of production in Spanish were Malaga, Seville, Valencia (Manises and Paterna), and Talavera de la Reina.

The influence of Italian majolica In 1492, Granada, the last Islamic state on the peninsula, fell into the hands of the christian kings; that was the end of the Reconquista. That, and the influence of the Renaissance coming from Italy, produced fondamental changes in the evolution of art and architecture, and in particular, in the azulejo. In Italy the technique of majolica had appeared; dishes and vases were produced with elaborate and colourful decoration: scrolls, foliage, characters, grotesque, etc. The city of Faenza, in central Italy, became an important production centre. So much so, that the name of the city gave the word « faïence » in French. There, tiles began to be decorated with an elaborate decoration. In 1498, an Italian painter of majolica came to settle in Seville, Francesco Niculoso, called Niculoso Pisano because he was from Pisa. He introduced in Spain the majolica technique and brilliantly applied it to azulejos. Until then, mono-chromatic tiles were cut and assembled, the colours were bright and applied with a uniform intensity. With the new Italian majolica style, tiles are painted like a wood panel or a canvas. And a variety of colours are used: blue, light yellow, dark yellow, green, brown, white, black, purple... What is particularly revolutionary, is the use of chiaroscuro, a use of contrasts of colours to achieve a sense of volume. From an almost industrial repetition of patterns, we move onto an artistic creation. Alicatado or cuerda seca tiles were made by craftsmen; azulejo panels are now painted by artists. The style of the azulejos is completely transformed: large decorated panels represent figurative and narrative scenes. Established in Seville, Pisano's influence was enormous throughout the peninsula: he was imitated in Toledo, Valencia, Talavera de la Reina, and also in Portugal. And it is in Portugal that this art will most prosper to the point of becoming one of the most characteristic art forms of the country. Another Italian majolica master had a significant influence on the art of tiles and architecture: Guido di Savino left Venice and settled around 1500 in Antwerp, in Flanders, then a Spanish province. Thanks to Guido di Savino, also known as Guido Andries, Antwerp became an important centre of production, and the majolica technique eventually diffused throughout Northern Europe (see www.delft.fr). The first French noted majolica maker is Masséot Abaquesne in Rouen. In the Netherlands, potters and majolica painters throve in Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Haarlem, Makkum and, of course, in Delft.

Styles following their times Styles of 16th century art express by a wide diversity of subjects: religion, hunting, war, mythology, etc. Painters of azulejos are freely inspired by ornamental prints from all over Europe, especially the grotesque: secular motifs of ancient Rome reinterpreted by Raphael to decorate the Vatican Palace. These grotesque are "fantastic" in the literal sense, and this theme will be widely reproduced and mixed with religious themes in particular. This is the time of trading with Far East; inspiration also comes from India and China. Exotic fabrics inspire tile painters to paint tile panels for the front part of altars in many Portuguese churches. At the end of the 17th century, the Dutch tile painters paint blue and white tiles and panels under the influence of Chinese porcelain. Chinaware is very expensive but much appreciated throughout Europe. Potters are trying to compete, and this produce faience "chinaware", especially in Delft. Portuguese aristocrats commission blue and white Dutch panels for their palaces and churches. Some Dutch tile makers will eventually settle in Portugal: Willem van der Kloet and Jan van Oort in particular. This type of blue and white azulejo will have much success in Portugal and soon in the 18th century, these panels will be imitated by Portuguese tile painters to the point that blue and white tiles will cover the entire country. This art was then at its peak, the mastery of azulejos painters is such that they often sign their panels. In the 18th century, the frames become more and more invaded by the baroque style and the entanglements of festoons, angels, and architectural elements. Then appears the rococo style, with again complex ornamentation. The decors are often inspired by Watteau and his engravings representing gallant, pastoral, and bucolic scenes, and promenades of aristocratic couples. After these frivolities, the 19th century promotes a return to the virtue and simplicity of the antique world. The style is known as "neoclassical". Tile panels are inspired by prints of Robert Adam and his brother James. The frames of the panels are simplified. This style marks especially the return to a rich polychromy.

Art Nouveau in France At the end of the 19th century, Art Nouveau appears in France and gives a boost to architectural ceramics, with the use of frost-resistant earthenware. The subjects represented are usually vegetal, with undulating and feminine movements. The influence of the posters of Alphonse Mucha and Eugene Grasset is obvious. The Exposition Universelle held in Paris in 1900 celebrated these architectural ceramics. The cloisonné process returned after several centuries of abandon. House facades, shops and restaurants are adorned with decorative tile panels, or more simply with friezes, often floral, sometimes in relief.

Nowadays, there is no more homogeneity of style in the creations of tile panels. They are mostly the work of one artist, seldom a ceramicist, who expresses himself occasionally by this art. The Lisbon subway stations or the Casa da Mùsica in Porto (architect Rem Koolhaas) show that it is in Portugal today where the use of ceramic in architecture is particularly alive.

Gallery Azulejos

-

Moorish cut tiles called alicatados

-

Moorish Palace in Spain : The Alhambra of Granada

-

Moorish tiles in cuerda seca technique

-

Moorish tiles in arista technique

-

Moorish tiles in Seville (Spain)

-

Sintra National Palace from the 16th c. (Portugal): The Lions room

-

Sintra National Palace: tiled fountain and bench

-

Sintra National Palace: patio

-

Sintra National Palace

16th c. -

Terracotta floors with inserted glazed tiles (Manises ou Paterna)

-

Blue tiles from the 16th c. in the National Museum of Palermo (Italy)

-

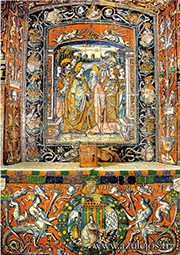

Tile panel painted circa 1500 by Francisco Niculoso for the Alcazar of Seville (Spain)

-

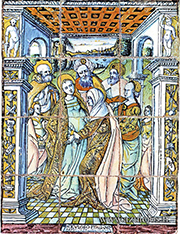

Tile panel painted circa 1500 by Francisco Niculoso and exhibited at Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam (Netherlands)

-

Mural azulejos in the Alcazar of Seville (Spain)

-

Colourful azulejos in the Alcazar of Seville (Spain)

-

Geometric azulejos in the Alcazar of Seville (Spain)

-

Renaissance tiles with grotesque

-

Ceramic panel Susanna and the elders painted in 1565 for the Quinta da Bacalhoa (Portugal)

-

Tile flooring of the Castle of Ribaute-les-Tavernes (France, Gard), 17th c.

-

Azulejos panel of the Basilica de la Virgen del Prado in Talavera de la Reina, 16th c. (Spain)

-

Wainscoting panels, Church of Paraiba (Brazil)

-

Tile panel with Medici vase, 17th c., Azulejo Museum of Lisbon

-

Azulejos panel with acanthus leaf motif, 17th c. (Museum of Decorative Arts, Paris)

-

Mural azulejos with acanthus leaf motif, 17th c. (El Escorial Palace, Madrid)

-

Pool with azulejos panels, Marqueses da Fronteira Palace in Lisbon

-

In The Fronteira Palace of Lisbon, gardens are adorned with numerous azulejo panels

-

Niches with azulejos, Palacio Fronteira in Lisbon

-

Mural tiles decorating the Palacio Fronteira in Lisbon

-

Bench covered with azulejos, Palacio Fronteira in Lisbon

-

Walls and ceiling decorated with ceramic tiles, Saint Lawrence Church in Faro, 1730 (Portugal)

-

Tiles decorating the ceiling of the Chapel of the Holy Spirit in Alenquer, late 17th c. (Portugal)

-

Monastery of Alcobaça, Lisbon (Portugal)

-

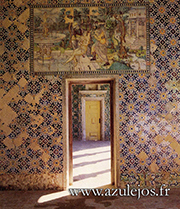

Door frame with trompe l'oeil azulejos, Braço de Prata Palace, Lisbon

-

Characters painted on tiles, Quinta da Videira, 18th c. (Portugal)

-

Tiles paneling with "Figura da convite", Casa Luis Gomes Pires, 1770 (Portugal)

-

Azulejo panel representing a human-size character (1780), Casal de Santa Maria, Colares (Portugal)

-

Azulejos, kitchen of Palacio Pimenta, Lisbon

-

Ceramic decor between chapel and sacristy, Palacio de Santos, now the French Embassy, Lisbon

-

Staircase decorated with azulejos, Palacio de Mitra, Lisbon

-

Azulejo panel inspired by an engraving of Watteau, Palacio Valada-Azambuja, Lisbon

-

Door ornated in trompe-l'œil, Saint-Paul Convent (Portugal)

-

Vault covered with tiles, Faro (Portugal)

-

Azulejo Cloister, convent of Sao Françisco, 18th c., Salvador de Bahia (Brazil)

-

Azulejo panels, Convent of Sao Francisco, Salvador de Bahia (Brazil)

-

Door with azulejo decor, Edouard VII Park, Lisbon

-

Crucifix painted on cut tiles (Portugal)

-

Clock painted on glazed tiles (Portugal)

-

Azulejos in the kitchen of the Convent of Saint-Dinis, Odivelas (Portugal)

-

Tiles panel painted in Holland by Jan van Oort (1698), Madre de Deus Convent, Lisbon

-

Azulejo panelling, Church of Mercy, Sardoal (Portugal)

-

Azulejos panel at Sao Vicente de Fora Monastery, Lisbon

-

Staircase decorated with azulejos at Sao Vicente de Fora Monastery, Lisbon

-

Azulejos "figura avulsa" at Obidos (Portugal)

-

Staircase decorated with azulejos at Sao Vicente de Fora Monastery, Lisbon

-

Tiled benches and columns, Quinta dos azulejos, Lisbon

-

Mural ceramic decor of a Valencian kitchen, 18th c., Decorative Arts Museum of Madrid

-

Decorative Arts National Museum of Madrid, tiles panel from the 18th c.

-

Spanish azulejos tile of folk art

-

Kitchen with "Pombaline" azulejos, 19th c. (Portugal)

-

Pombaline azulejos, 19th c. (Portugal)

-

Ceramic facade, Quinta da Sao Mateus at Oeiras, 1860 (Portugal)

-

Via crucis (Way of Sorrows), painted on tiles in 1752 (Portugal)

-

Neo-classical azulejo panel, late 18th c. (Portugal)

-

Neo-classical azulejos, Solar do Conde dos Arcos, Salvador de Bahia, 1800 (Brazil)

-

Tiled wall and columns, Temple of San Francisco Acapetec, Cholula (Mexico)

-

Tiled facade, Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe Church, Puebla, 20th c. (Mexico)

-

Santa Maria Tonanzintla at Puebla, 18th c. (Mexico)

-

Neo-classical tile facade of the ceramics factory Viuva Lamego, Lisbon (Portugal)

-

Tile factory Viuva Lamego in Lisbon, 19th c.

-

Aveiro Railway Station with azulejo decoration (Portugal)

-

Azulejos in Vilar Formoso Railway Station (Portugal)

-

Azulejos from the 20th c. in the Place of Spain, Seville

-

Street sign from the 20th c., today in the City Museum of Lisbon

-

Painted tiles (Portugal)

-

Street sign painted on tiles (Portugal)

-

Street sign painted on tiles (Portugal)

-

Street sign painted on tiles (Portugal)

-

Stair risers, Plaza de toros, Ronda (Spain)

-

Fountain decorated with azulejos, Agres (Spain)

-

Fountain decorated with azulejos (Spain)

-

Azulejos in Santo-Antonio Convent, Cairu (Brazil)

-

Azulejos in the subway station Campo Grande, Lisbon

-

Modern azulejos, late 20th c., Lisbon

-

La Casa da Mùsica with azulejos panels (Rem Koolhaas architect), Porto

-

Azulejos in the subway station Oriente, Lisbon